Alvin Weinberg archive opens window into Cold War nuclear science

Alvin Weinberg has an incredible resume, if you will.

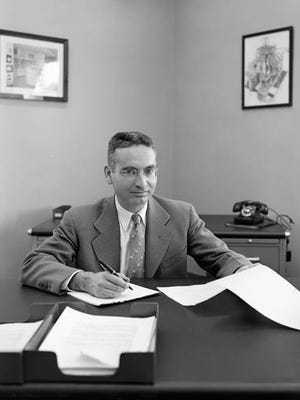

He came to Oak Ridge in 1945 as a Manhattan Project scientist and stayed in the city until his death in 2006. He was an influential nuclear physicist and the longest-serving director of Oak Ridge National Lab, home of some of the country’s most important scientific achievements. He was a scientific bridge between the use of the nuclear bomb to the importance of climate change.

But the personal stories behind the man are far, far more interesting.

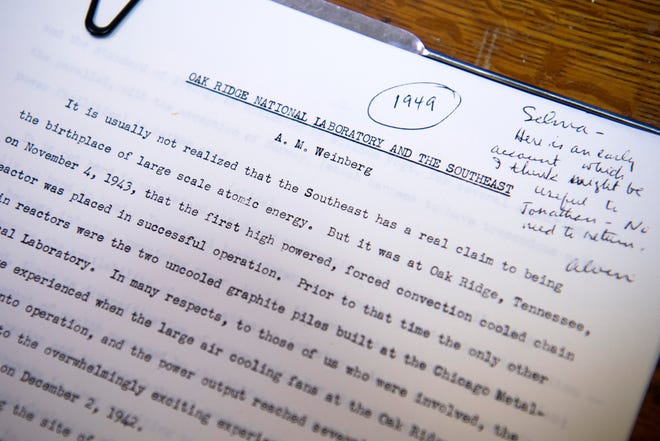

His impact on science, and on scientific thinking in general, are becoming more appreciated through the digital publication of his voluminous handwritten letters. They not only get into the nitty-gritty of nuclear science and Oak Ridge, they expose the deeply philosophical conversations Weinberg was having about the power and danger of nuclear energy in the years after the Oak Ridge-developed bomb dropped on Japan to end World War II.

“We nuclear people have made a Faustian Bargain with society. On the one hand we offer … an inexhaustible source of energy,” Weinberg wrote in an address to nuclear scientists. “But the price we demand of society for this magical source is both a vigilance and longevity of our social institutions that we are quiet unaccustomed to.”

Alvin Weinberg sidebar: A look into the personal writings of Alvin Weinberg, the Cold War leader of ORNL

From the archives:Atomic super-bomb, made at Oak Ridge, strikes Japan

In an unusual arrangement based on personal ties, the Children’s Museum of Oak Ridge has nearly completed the digitization of hundreds of thousands of documents from Weinberg’s personal archive of correspondence, papers and writings. It is housed at childrensmuseumofoakridge.org/weinberg.

“I think we do not even remotely recognize the importance of what has been done to make these papers generally available,” local historian Ray Smith told Knox News. “In the years to come, researchers will be thankful to find such a rich archive a one of the pioneers of the Nuclear Age.”

The digital archive is preserved in Weinberg’s original filing system, organized by topic. It contains everything from handwritten notes to rough drafts of public speeches. Photographs of Weinberg with partners, friends and acquaintances are scattered through digital folders.

Browsing the collection feels like rifling through someone’s eccentric filing system.

Sometimes the contents are surprising. In a folder about civil defense research, there is a letter where Weinberg reacts with horror to the use of air-fuel bombs on Vietnamese villages. In a folder of correspondence with Japanese scientists, you’ll find travel brochures to Tokyo and a heartfelt condolence to the spouse of a dead scientist.

Precedents set by Alvin Weinberg

When looking back with the perspective of time, Weinberg’s biggest impact centers on how large scientific organizations organize and present themselves.

He was among the first and loudest commentators to point out that big research institutions, by necessity, had to focus on research that affected people’s daily lives. This philosophy and commitment to big, responsible science is all over his personal writings.

“Everywhere there is a restlessness and concern,” wrote Weinberg. “We must abjure our preoccupation with hard science and address ourselves to these subtler, more difficult and more important human problems.”

Weinberg is widely credited with saving Oak Ridge National Lab from the post-Manhattan Project chaos that embroiled the lab after World War II. But more importantly, Weinberg was perhaps one of the loudest and most influential voices in the scientific community during the Cold War.

His belief that the federal government should sponsor large research projects that address national and international issues became the ideological foundation for Oak Ridge National Lab and the national lab system as a whole.

“His interest is so wide and driven by a desire to help humanity that comes through vividly in these files,” said Ronnie Bogard, the archive project lead for the museum. She hopes to be done digitizing by the end of the year.

The archive opens a digital window to the Cold War era of the lab and its transition into a scientific institution. The digital archive will be available for students, historians and curious researchers to use in perpetuity without the risk of damaging the original documents. Weinberg left the documents to the Children’s Museum because of his close friendship with the museum’s founder, Selma Shapiro.

“Alvin gave her the papers because she had such a focus on the history of Oak Ridge,” Bogard explained.

Alvin Weinberg’s life and work

Weinberg was the son of Russian Jewish immigrants who met on a ship travelling across the Atlantic. They would settle in Chicago, where Weinberg was born and raised. According to Weinberg’s son, Alvin was not like his parents. Weinberg’s mother was loud, boisterous and dramatic while he was more gentle and reserved.

My grandmother was this over-the-top emotional Russian babushka kind of figure,” Richard Weinberg told Knox News. “I expect he was sort of reacting to that.”

Like the majority of scientists in the international physics community, Weinberg was absorbed into the Manhattan Project in the 1940s. He was a young scientist, having only completed his doctorate a few years before being brought into the now-famous Chicago Metallurgical Lab to secretly help design plutonium reactors.

Weinberg’s calculations would go into designing the X-10 Graphite Reactor at Oak Ridge, the world’s second successful nuclear reactor. It was this reactor that would supply the lab in Los Alamos, New Mexico, with its first samples of plutonium for nuclear weapon design work.

Another Weinberg reactor design, the pressurized water reactor, ultimately became the most used nuclear reactor design for nuclear power plants.

n 1945, Weinberg followed Eugene Wigner, his mentor and a key Manhattan Project physicist, to Oak Ridge. There Weinberg was promoted to the head of the Physics Division.

After World War II ended and the Manhattan Project was completed, the fate of the lab — and the city of Oak Ridge — were uncertain. The lab’s management shifted from the U.S. Army to the Atomic Energy Commission, which shuffled through several different contract administrators. Staff scientists began to leave for other laboratories. There were plans for all of the nuclear reactor work to be transferred to other locations.

It might seem strange now, but the future of large-scale, government-funded science was not certain at the time. The national lab system, in its entirely, grew out of the Manhattan Project, which was singularly focused on developing atomic weapons. With that mission done, it was not clear what those experts would do.

“They faced an existential crisis,” said Richard Weinberg, whos is a neuroscientist. “You could make a strong argument that they should have been disintegrated.”

Richard Weinberg said that while many national labs continued to try to push for additional nuclear weapons research, his father saw things differently.

“If they were going to do anything, they’d better move on to topics that are not thermonuclear warfare,” he said.

After several other prominent figures left in the late 1940s for other research positions, Weinberg stepped into the role of research director and eventually director of Oak Ridge National Lab in 1955. Weinberg stepped up and struck an agreement with the director of Argonne National Lab near Chicago, carving out space for Oak Ridge to continue reactor research.

The lab itself credits this move with saving the lab from closure.

“The deal was a boon for Oak Ridge, which would build 13 special-purpose research reactors in all,” Tim Gawne wrote in the 75th anniversary edition of Oak Ridge National Laboratory Review. “His brilliance was often turning iffy situations into gold.”

The growth of the lab

Under Weinberg’s leadership, the lab expanded dramatically, particularly the Biology Division, which grew five times in size. During his tenure the Oak Ridge ecology program began. Some of the earliest mRNA studies, the same type of RNA that is used in COVID-19 vaccines, were conducted under his leadership. The use of radiation therapy for cancer treatment was pioneered under his leadership. The cancer-treating isotopes were made at Oak Ridge.

Much of this biological research was fueled by Weinberg’s deep commitment to responsible nuclear power. Weinberg famously called nuclear power a “Faustian bargain,” requiring extraordinary vigilance from nuclear scientists to avoid paying the price of a reactor meltdown or waste spill.

“He took life very seriously, for him one of the dirtiest names you could call somebody was irresponsible,” said Richard Weinberg.

His commitment about nuclear safety were part of what led President Richard Nixon to fire him in the 1970s, ending his 18-year tenure as the head of the lab. Weinberg had raised repeated concerns about safety of nuclear power plants, which were at odds with Nixon’s nuclear energy policy.

“My ideas about nuclear energy were, I guess I’d say, orthogonal to the mainstream of ideas,” Weinberg said in an oral history project. “My very good friend, John Swartout, who was my deputy director … he took me aside one day and said, ‘Alvin your time is up.'”

Climate change and Big Science

After he was fired by Nixon, Weinberg devoted himself to climate change. He was one of the earliest advocates sounding the alarm on climate change. For the majority of the remainder of his life, Weinberg would lead the Institute for Energy Analysis at Oak Ridge on energy and environmental policy.

“Alvin got really engaged early in the concerns of global climate change,” said Gregg Marland, a geologist who worked with Weinberg at the institute. “He thought climate change was going to drive people away from fossil fuels and ultimately the answer had to be nuclear power.”

The growth in the lab, and the shift to climate change, reflected Weinberg’s personal philosophy of science. He believed scientists should try to address large, pressing social issues and think beyond the narrow confines of their specific disciplines. Such projects required a lot of collaboration and infrastructure to achieve.

Weinberg called this kind of science “Big Science.”

“Big Science, as people like Weinberg were thinking about it, involve this idea of not asking disciplinary questions,” said Audra Wolf, a historian of science and author of “Freedom’s Laboratory,” a history of Cold War science. “Instead, they asked problem-based questions and put together interdisciplinary departments that could look at specific problems.”

Wolf says that this kind of thinking began to emerge in the 1960s and ’70s in the national lab system. It has since become one of the dominant strains of scientific investigation worldwide.

Big Science still dominates the national lab system to this day. The fingerprints of Weinberg’s Big Science idea are on everything from the Summit Supercomputing System to the Aquatic Ecology Lab in Oak Ridge.

“He encouraged (Big Science),” said Wolf. “He gave a name to something that people didn’t know what to call it.”

Big Science in democracy

While Weinberg promoted this kind of science at the national lab, he was worried about how it would function within a democratic society and whether it would destroy science broadly. When science gets that big, research questions become political questions. For Weinberg, this qualitatively changed the nature of science from one of curiosity to politics. That change could “infect” the rest of the scientific enterprise if left unchecked.

“We do the best we can, however; and at least, by confining Big Science to such (national) institutions, we prevent the contagion from spreading,” Weinberg wrote in a 1961 article.

Anxieties about the growth of state-sponsored science were widespread, Wolf said. During the Cold War, the United States and Soviet Union were competing everywhere, including in science. Americans adopted a scientific posture of being “empirical, international and separate from government control.”

That posture was at odds with Weinberg’s experience with science as the administrator of a large, government lab.

“I do believe that Big Science can ruin our universities … by converting university professors into administrators, housekeepers and publicists,” Weinberg wrote in Science magazine.

Wrestling with questions science can’t answer

For Weinberg, the unchecked growth of Big Science could lead to asking moral or political questions of science — questions that Weinberg did not believe science was able to solve. He called this “trans-science.”

“The deleterious side of effects of technology or the attempts to deal with social problems through the procedures of science hang on the answers to questions which can be asked by science and yet which cannot be answered by science,” he wrote.

Weinberg himself was not immune from getting caught up in what he called trans-science. This sometimes happened when he was trying to avoid moral or social questions by promoting technological solutions.

Science historian Sean Johnston points out that in promoting scientific solutions to national problems, Weinberg often fell into a kind of pattern similar to what is seen today in Silicon Valley, which is reducing complex problems to technical issues.

In correspondence with Emmanuel Mesthene, a renowned philosophy professor at Harvard, Weinberg said that he believed nuclear weapons themselves were a “cheap fix” for the problem of human violence.

In the same letter, Weinberg floated the idea of using air conditioning to reduce the likelihood of race riots in Los Angeles.

“Admittedly this is a superficial and possibly heartless approach to the problem; yet it has the advantage that it just might work.” Weinberg wrote.

That impulse survives to this day. It’s not so different from promising to prevent COVID-19 transmission with an app, or fixing educational disparities entirely through game design as some startups have proposed.

“Weinberg’s seductive notions were mainstreamed to shape the confidences of those seeking solutions to novel and enduring societal problems,” wrote Johnston.

While Weinberg thought of himself as a “tech fixer,” and half-jokingly refers to himself that way his autobiography, even as he grappled with the limits of what science could be asked to solve.

Weinberg, unlike many scientists and administrators, discussed his feelings on Big Science in public with nearly anyone who would talk to him.

Johnston, the science historian, said that the archives are invaluable for seeing into a time in history that has had an incredible, but unstated, impact on our contemporary understanding of science and technology.

“I commend the digitization project participants for opening a window in what has been a shadowy corner,” wrote Johnston in an email to Knox News. “The Children’s Museum at Oak Ridge Alvin Weinberg archive is a rare snapshot of recent American history.”

Comments are closed.