Peace with Iran and North Korea Would Help U.S. Workers

When the now-retired Republican Senator Bob Corker cut U.S. arms sales to Saudi Arabia in 2017, White House trade adviser Peter Navarro penned a memo entitled “Trump Mideast Arms Sales Deal in Extreme Danger, Impending Job Loss”. The memo, along with the Trump administration’s later decision to lift the lockdown, is often referred to as a cynical compromise: billions of dollars in military hardware helped sustain a humanitarian crisis in Yemen, but those dollars could also help Supporting thousands of American jobs. Given the choice between domestic workers and human rights abroad, the Trump administration appeared to have put America first.

But bombs aren’t the only thing American workers can build for the Middle East. Just as President Donald Trump was boosting arms sales in the Gulf, he was also working to kill the Iranian nuclear deal. A key part of this deal was economics – when the sanctions were lifted, Western companies were able to help rebuild Iran’s aging civil infrastructure by resuming trade and investment in Iran. One of the earliest contracts Iran signed was for American aerospace maker Boeing 110 to build around $ 20 billion worth of jumbo jets to revive Iran’s civilian air fleet. The estimated nearly 20,000 U.S. manufacturing jobs that the civil contract could have created was strikingly similar to the number associated with the Saudi arms business. However, they ended when Trump pulled out of the Iran deal and re-imposed sanctions.

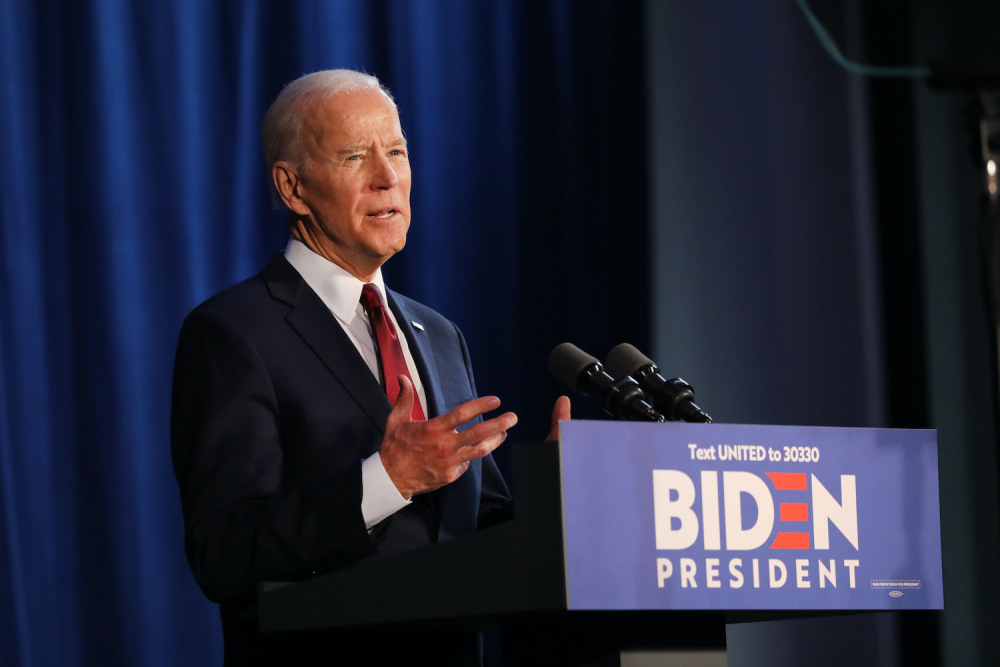

These two episodes show what a turning point for US foreign policy could be. Trump and his challenger Joe Biden both battled for promises to revitalize U.S. manufacturing and reduce U.S. military intervention overseas. For the past four years, both Trump and his critics have made the wrong compromise between these efforts by overlooking the economic dimensions of US diplomacy. Now that Biden is president, his government can either accept this false compromise or draft new guidelines that will serve his national and diplomatic agendas together. One of his greatest foreign policy challenges is to bring Iran and North Korea back into contact, two countries whose regimes have been seeking political and economic ties with the West for decades.

Under US sanctions, Iran and North Korea’s infrastructures are in poor shape, their resource sectors are underdeveloped, and their populations are largely cut off from Western economies. Without sanctions, however, Western companies could capitalize on untapped opportunities in sectors such as oil and mineral extraction, transportation, and port infrastructure, much of which would include industrial equipment that US workers could build at home.

Linking diplomacy to domestic business could help address a fatal flaw in previous non-proliferation treaties: the United States generally lacks significant domestic interest groups with a vested interest in implementing America’s diplomatic commitments. In the case of the Iran deal, this meant that while the Obama administration had put considerable political capital into working out an effective solution to the Iranian nuclear crisis, the subsequent Trump administration would have little political cost if it gave up.

Another promising non-proliferation agreement – the 1994 framework that seriously undermined North Korea’s nuclear program – suffered a similar fate when a hostile George W. Bush administration took office and sank it. In both cases, American negotiators focused on enforcing strict nuclear restrictions to prevent fraud from the other side, but failed to ensure the implementation of US commitments or protect their diplomatic achievements from future US administrations.

Had these deals been better tied to domestic economic benefits, they might have been more resilient in the face of changing political tides. Today, with the credibility of U.S. non-proliferation diplomacy in ruins, other governments will expect a Biden administration to make future-proof U.S. commitments by cultivating supporters of diplomacy at home.

But could a country’s economic development help curb its nuclear program? History suggests that this is possible, and the agreed framework is an illustrative case. In this agreement, North Korea agreed to dismantle its plutonium production reactors in exchange for civilian power reactors from the West. North Korean negotiators explicitly described the civilian reactor project as an “indication of good faith in the US” and as a sign that the US government could end its “hostile policy” towards North Korea. When the civil reactors began to be built, the regime essentially gutted its plutonium infrastructure. This suggests that economic engagement can help make a regime feel less committed to nuclear weapons.

Critics of the engagement will reject any policy that appears to reward a country for simply adhering to international non-proliferation norms that the rest of the international community already respects. However, this misses the point of economic diplomacy. Experts have long warned that the United States must fundamentally change its relations with these countries in order to really resolve the nuclear proliferation crisis in Iran and North Korea.

The trick, however, is that after decades of hostility and unpredictable politics, U.S. negotiators cannot simply promise to change those relationships. Instead, the US government must commit an ongoing act that goes beyond words and written agreements.

In the case of the framework agreed in 1994, this was the point at which civil power reactors were built in North Korea. In the words of one US diplomat, nuclear reactors are “not the kind of things a country gives an enemy,” and if those reactors were fully built, the United States and its regional allies would be “hardwired into the technology and the world “The economic relationships that would be required to operate these reactors in North Korea safely. The steps to build the reactor thus signaled that if the agreed framework survived, the United States would ultimately normalize diplomatic relations with North Korea, which is what the regime needed to feel secure in withdrawing its nuclear weapons program.

A similar opportunity was missed with Iran in the 1990s when Iranian President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani tried to partner with US oil company Conoco to expand its oil infrastructure. His political goal was to facilitate a permanent form of Iranian-American engagement to pave the way for broader reconciliation, and US-based opponents of that reconciliation have quickly thwarted his plan. But relations between the US and Iran could be different today if this project had been taken forward.

Such physical investments, if properly planned and implemented, could spark a common interest in maintaining more positive relationships beyond partisan policies in Washington and regime policies in Tehran and Pyongyang. And they can send a more credible signal that a nuclear rollback will lead to a secure and prosperous future that the US government has promised in previous non-proliferation diplomacy campaigns.

As Biden tries to re-involve Iran and North Korea, he should try to establish some form of economic diplomacy that will outlast his administration. And infrastructure investments that boost both non-proliferation goals and American jobs could finally do the trick.

Ironically, the Trump administration may have left Biden with the perfect vehicle for connecting diplomacy to US manufacturing: a revitalized US export-import bank. While Trump re-authorized Ex-Im Bank as part of his strategy to combat China’s Belt and Road initiative, it could be key to linking non-proliferation diplomacy to U.S. manufacturing.

When the Iran deal was signed and western companies wanted to do business in Iran, the main obstacle was that big banks refused to fund their projects for fear that sanctions might be re-imposed. The Boeing deal was one of the contracts that was delayed because of this. Facilitating some of these transactions must be an integral part of reviving the Iran deal. Ex-Im Bank now specializes in drawing international transactions that benefit US workers, and it has a long history of empowering US companies in precisely those sectors that need to be developed in Iran.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in has already proposed a number of ambitious development projects in North Korea under the heading “New Economic Map”. However, these projects are currently sanctioned. In the event of renewed negotiations between the US and North Korea, the Biden government should not only put sanction relief on the table, but also offer ex-im-bank financing for some of these projects in exchange for nuclear rollback steps in North Korea. For example, if US funding could help develop North Korea’s mining infrastructure to develop rare earth mineral resources, it could give North Korea a new and influential role on the world stage that does not depend on nuclear weapons. At the same time, the US government could tie the final completion of these projects to future rollback steps.

In both Iran and North Korea, economic engagement that links non-proliferation diplomacy to U.S. jobs offers the most promising way to roll back nuclear programs and motivate future governments to continue building on U.S. diplomatic achievements rather than wasting them and starting over .

Comments are closed.