The Air Force Once Flirt With Basing New ICBMs in Lakes, Tunnels

- The US Air Force considered a number of new basing techniques for its forthcoming LGM-35A Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile.

- Sentinel will make up the land-based portion of the Pentagon’s nuclear triad.

- The service considered deploying Sentinel underwater or in a vast maze of underground tunnels.

The US Air Force is preparing for a new nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missile, and a newly-released document shows the service was open to some pretty…unusual…basing schemes. That included deploying the missiles in “deep lakes” or in underground tunnels, but the Air Force ultimately abandoned both ideas. It goes to show how hard it is to base 400 nuclear-tipped long-range missiles—missiles that everyone wants to kill, and nobody wants to live by.

On July 1, the Federation of American Scientists first brought the document, Draft Environmental Impact Study for the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (an earlier name for the LGM-35A Sentinel), to the public’s attention. The Federation is a Washington, DC-based nonprofit global policy think tank with the stated intent of using science and scientific analysis to attempt to make the world more secure.

The 954-page document is meant to investigate the possible environmental consequences of basing the Sentinel missile and demolishing old Minuteman III missiles. It covers subjects including the environmental impact of new construction, hazardous materials handling, and possible effects on local wildlife, including grizzly bears and the little brown bat.

On one level, the idea that an environmental impact report is needed for a new intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) seems bizarre. In a nuclear war with a major nuclear power, enemy ICBMs would target any Sentinel missile location, and the nearby environment would be completely destroyed. Yet such a war is merely possible, and in reality, extremely unlikely. Meanwhile, life goes on, and the environment needs protecting from the imminent deployment of 400 new nuclear-tipped missiles.

An LGM-30 Minuteman I intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is launched from Launch Facility 6 at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California, 2000. The missile is unarmed.

HUM imagesGetty Images

Land-based ICBMs are just part of a nuclear triad that includes submarine-launched missiles and long-range bombers. ICBMs are considered the most accurate and most responsive, capable of lifting off from their silos less than five minutes after receiving the order to launch. From there, it’s about a half-hour trip across the globe to North Korea, Russia, and China. The quick-launch capability makes ICBMs an early target in a nuclear war.

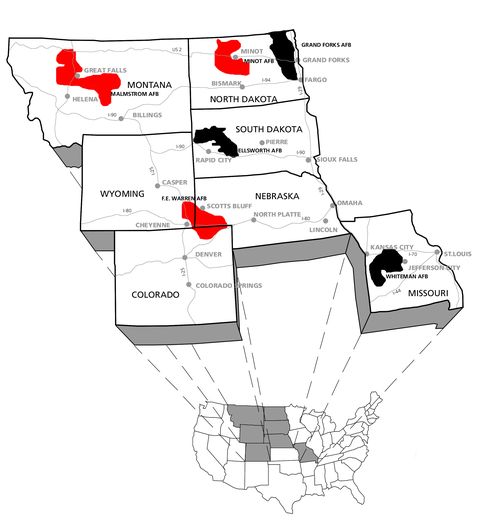

For the better part of a century, military planners, policymakers, and engineers have been vexed by the question of where and how to base large, land-based missiles bristling with nuclear weapons. The missiles must be based in a way that deters the enemy from attacking them, or that ensures their survival in a first strike, all while keeping them easily accessible and quick to fire. The missiles must also be placed away from civilian population centers, and must operate within environmental guidelines. For now, the existing 400 Minuteman III missiles are based in silos scattered across the American West, in states like Wyoming, Montana, North Dakota, and Nebraska.

✅ Get the Facts: In the Event of Nuclear War

The environmental impact study makes clear that the Air Force is considering new basing schemes for the LGM-35A Sentinel. One such scheme was the use of “deep lake” tethered basing. In this scenario, the Sentinel missile is placed in a waterproof capsule that is anchored to the bottom of a deep lake. Once the order is given to launch, the capsule is released, rushing to the surface, whereupon the missile rocket motor ignites and the Sentinel missile crawls skyward.

The locations of Minuteman missile silos across the United States. The fields marked in black were deactivated and no longer host missiles, the fields marked in red are still active.

National Park Service

Deep-lake basing is an interesting idea, partially recycled from a Cold War plot to base missiles in the Great Lakes. The lack of many deep lakes in the continental United States means under this plan, Sentinels probably would be deployed in the Great Lakes. Another possibility is Lake Tahoe on the California/Nevada border.

According to the study, deep-lake basing was abandoned for several reasons. For one, the missile and its thermonuclear warheads would be at the bottom of lakes, and thus less secure from tampering, theft, and terrorism than if they were being stored inside a hardened concrete silo. The scenario was also described as “cost prohibitive”; not only would the Air Force need to develop the underwater silos, it would need an entirely new water-based infrastructure for maintaining and deploying the missiles.

At a depth of 1,644 feet, Lake Tahoe is an obvious choice for “deep-lake” ICBM basing. Whether or not people want to paddle board above nukes is another question.

George RoseGetty Images

A third reason the scheme was abandoned: it was described as having “extreme or insurmountable environmental consequences,” no doubt from the prospect of storing plutonium and rocket fuel in a thin metal tube in the drinking water of untold numbers of people. In the event of an accidental release of radiation or toxins, cleanup could be astronomically expensive and turn public opinion against nuclear weapons.

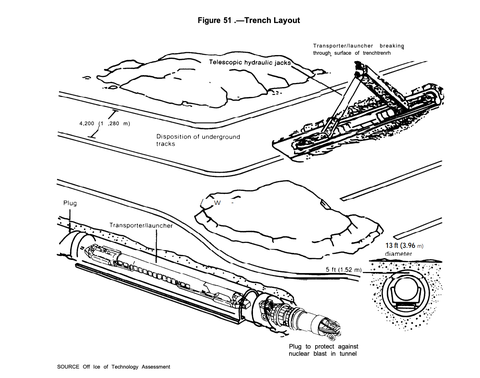

The second basing study, on “underground tunnel systems,” would replace stationary concrete silos with “likely hundreds” of underground tunnels connected by a rail system. The missiles would ride the rail system on launchers and, in the event of attack, would push up through the dirt above and then ignite their engines.

In the 1980s, the US government studied underground basing as a deployment scheme for the then-new MX, or Peacekeeper, missile system.

Office of Technology Assessment via The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

Underground tunnel systems work by inducing “location uncertainty”: instead of making it harder to destroy a fixed target, like a land silo, it makes it hard to know where the true target, the missile, is at any point in time. The missiles are more vulnerable, but arguably safer from attack, forcing an enemy to expend vast numbers of nukes in an attempt to destroy the tunnel system.

The Air Force also abandoned tunnel basing for being prohibitively expensive: the service would need to dig hundreds of miles of shallow tunnels, while ensuring they are structurally sound, and set up new infrastructure to maintain both the rail network and the missiles. Tunneling was also anticipated to have “extreme or insurmountable environmental consequences,” though what those consequences could be was left unsaid. Possibly, the Air Force was concerned that grizzly bears would fall into them, or they would become little brown bat havens.

Airmen from the 90th Maintenance Group maintaining a Minuteman III ICBM, December 2019.

US Air Force photo by Senior Airman Abbigayle Williams/DVIDS

In the end, the Air Force elected to merely install the new Sentinel missiles in refurbished Minuteman III silos. Reusing the silos is cheaper, easier to maintain, and secure. Perhaps just as importantly, the nukes are out of sight and out of mind. Plus, boaters on Lake Superior won’t be troubled by the prospect of sailing directly above hundreds of megatons of nuclear firepower. Because if people truly understood what those weapons could do, we might actually want nothing to do with them.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

Comments are closed.