The competition is heating up in a melting Arctic

[By Rockford Weitz]

For decades, the frozen Arctic has been little more than a footnote in global economic competition, but that’s changing as its ice melts as the climate warms.

Russia is now trying to claim more of the Arctic seabed for its territory. It has rebuilt Cold War-era Arctic military bases and recently announced plans to test its nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed torpedo Poseidon in the Arctic. In Greenland, the recent election ushered in a new government for independence, opposed to overseas mining of rare earth metals as the ice sheet retreats – including projects that China and the US are counting on for energy supplies.

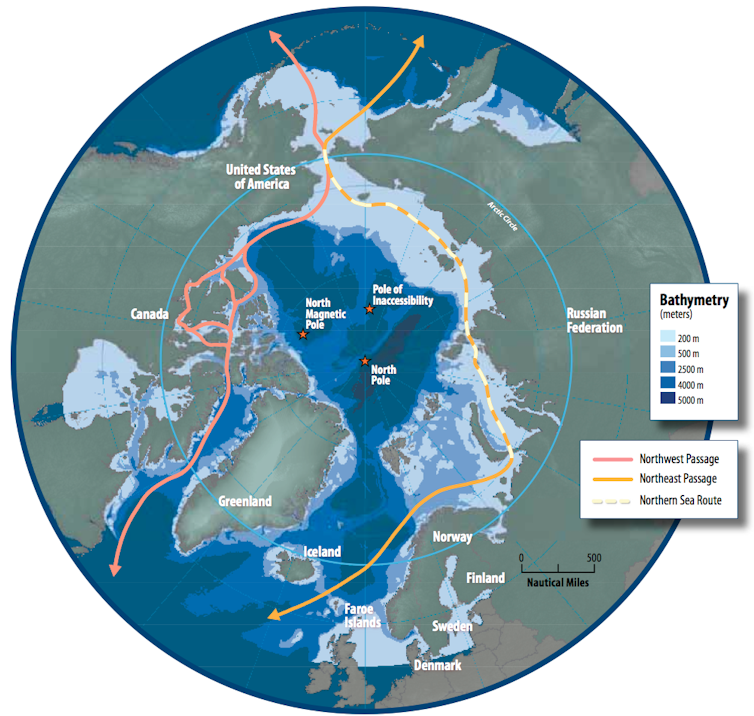

The Arctic region is warming at least twice as fast as the planet as a whole. With sea ice now thinning and disappearing earlier in the spring, several countries have been keeping an eye on the Arctic, both for access to valuable natural resources, including fossil fuels, the use of which is now driving global warming, and as a shorter path for commercial ones Purposes ships. A tanker transporting liquefied natural gas from northern Russia to China tested this shorter route last winter and in February crossed the normally frozen North Sea route for the first time with the help of an icebreaker. The route cut shipping time by almost half.

Arctic Shipping Routes (Susie Harder / Arctic Council)

For these and other purposes, Russia has been building its icebreaker fleet for years. The USA are meanwhile playing catch-up. While Russia now has access to more than 40 of these ships, the US Coast Guard has two, one of which is well beyond its intended useful life.

As an expert in maritime trade and Arctic geopolitics, I follow the increasing activity and geopolitical tensions in the Arctic. They underscore the need to rethink US Arctic policy in order to face emerging competition in the region.

The problem with America’s icebreaker fleet

America’s aging icebreaker fleet is a persistent subject of frustration in Washington.

In the face of more pressing demands, Congress has postponed investments in new icebreakers for decades. Now, the lack of polar-class icebreakers is undermining America’s ability to operate in the Arctic, including responding to disasters as shipping and mineral exploration increase.

It may sound counterintuitive, but decreasing sea ice can make the region more dangerous – breaking ice floes pose risks to both ships and oil rigs, and the open waters are likely to attract both more shipping and more mineral exploration. The US Geological Survey estimates that about 30% of the world’s undiscovered natural gas and 13% of the world’s undiscovered oil are in the Arctic.

The Polar Star icebreaker is 45 years old and needs to be replaced (Mariana O’Leary / US Coast Guard)

The U.S. Coast Guard only has two icebreakers to handle this changing environment.

The Polar Star, a heavy icebreaker that can break ice up to 21 feet thick, entered service in 1976. It is usually sent to Antarctica in winter, but this year it was sent to the Arctic to provide a US presence. The crew of the aging ship had to fight fires and deal with power outages and equipment failures – all in some of the most inhospitable and remote places on earth. The second icebreaker, the smaller Healy, which entered service in 2000, suffered a fire on board in August 2020 and suspended all Arctic operations.

Engineers aboard the Polar Star repair a salt water pump in the Bering Sea on January 28, 2021 (Cynthia Oldham / US Coast Guard)

Congress has approved the construction of three more heavy icebreakers at a total cost of approximately $ 2.6 billion and has funded two of them so far, but it will take years to manufacture. A Mississippi shipyard expects to ship the first by 2024.

An icebreaker solution

One way to expand the icebreaker fleet would be for allies to jointly procure and operate icebreakers while everyone is still building their own fleet.

For example, the Biden government could work with NATO allies to create a partnership modeled on NATO’s strategic airlift capability for C-17 aircraft. The airlift program, launched in 2008, operates three large transport aircraft that its 12 member states can use to quickly move troops and equipment.

A similar program for icebreakers could be operated by a fleet under NATO – perhaps starting with icebreakers contributed by NATO nations like Canada or partner countries like Finland. As with the Strategic Airlift Capability, each member country would purchase a percentage of the operating hours of the joint fleet based on its total contributions to the program.

Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin announced on June 9, 2021 a move towards more of this kind of collaboration and plans to establish a new Center for Arctic Security Studies, the Department of Defense’s sixth regional center. The centers focus on research, communication and collaboration with partners.

Apply the law of the sea

Another strategy that could strengthen the US’s influence in the Arctic, cushion impending conflicts and help clarify claims on the seabed would be the ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea by the Senate.

The law of the sea came into force in 1994 and laid down rules for the use and exchange of oceans and marine resources. This also includes determining how countries can claim parts of the ocean floor. The U.S. initially objected to a section that restricted deep-sea mining, but that section was modified to address some of those concerns. Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama all called on the Senate to ratify it, but they still haven’t.

Ratification would give the US a stronger international legal position in contested waters. It would also allow the US to claim more than 386,000 square miles – an area twice the size of California – of the Arctic seabed along its extensive continental shelf and stave off other countries’ overlapping claims to the area.

Without ratification, the US will be forced to rely on customary international law in pursuing any maritime claims, which weakens its international legal position in contested waters including the Arctic and South China Seas.

Dependent on international cooperation

The Arctic was generally a region of international cooperation. The Arctic Council, an international body, has left eight countries with sovereignty over land in the region, focusing on the fragile Arctic ecosystem, the welfare of indigenous peoples, and emergency prevention and response.

In recent years, however, countries “near the Arctic” including China, Japan, South Korea, Great Britain and many EU members have become more involved and Russia has become more active.

With increasing tensions and growing interest in the region, the era of cooperative engagement with the melting sea ice begins to recede.

Rockford Weitz is Professor of Practice, Entrepreneur Coach, and Director of the Maritime Studies Program at Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

This article is courtesy of The Conversation and can be found here in its original form.

This article has been updated with the announcement by the Department of Defense on June 9, 2021 that it will establish a new center to promote cooperation in the Arctic.

The opinions expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.

Comments are closed.