Will nuclear waste ever be as welcome in Switzerland as it is in Sweden?

This field in in Stadel, canton Zurich, is set to be the entrance to the deep geological repository. Highly radioactive waste is to be stored here for up to a million years. Keystone / Michael Buholzer

After years of searching, a site has been chosen to store Switzerland’s nuclear waste. Sweden is a step ahead: there, most local residents actually support construction.

This content was published on October 14, 2022 – 09:00

No one was happy with the decision. “Do you imagine we applauded when we heard the news? Not in the slightest!” said local mayor Dieter Schaltegger at the information meeting where people were making their discontent known.

It was only a few days since he had been told what was coming for his village and the whole Nördlich Lägern region in canton Zurich: Switzerland’s nuclear waste is going to be buried there. The decision was taken in mid-September 2022; getting over political hurdles is likely to take another ten years. Construction should start on the permanent repository in 2045.

It has provoked a reaction in the region – and all over Switzerland. No one knows for sure if and when building will really start on the designated piece of land near the German border. Technical decisions are still being made. NAGRA, the national agency for storing radioactive waste, has been looking for the right place for about 50 years. An initial plan to put it in central Switzerland was defeated in referendums.

NAGRA has learnt its lesson, says spokesperson Patrick Studer. “We did not communicate enough before,” he admits. The result was that the local population was always dead against it – wherever they did exploratory digging.

“Now we know how important it is to take critical arguments seriously,” he says, explaining that this is something NAGRA learnt mainly from the “communication pioneers, Sweden and Finland”, where governments managed to create “an atmosphere of trust”.

On site in Sweden

Sweden began its search for a location several years after Switzerland – and is now decades ahead. Since 1992 Sweden has had a permanent repository for low- and intermediate-level radioactive waste. The repository for highly radioactive waste is due to open in the very same locality in 2035.

The Swedish geological repository is being built here under the offshore island swissinfo.ch

In the community of Östhammar, the permanent repository has a current approval rating of 84%. What’s more, 39 of 49 elected local officials came to the conclusion that with these figures there is no need for another referendum. It was a condition for acceptance of the first permanent repository that the people have a veto on any extensions. But local mayor Jacob Spangenberg suggested that no further referendum needed to be held.

Spangenberg himself has a critical attitude to atomic energy. He belongs to a party which in 1980 voted for Sweden’s long-term withdrawal from nuclear power. For Östhammar, this permanent repository means taking responsibility for “one of the main environmental issues in our time”, Spangenberg believes. If Sweden were to build new nuclear power stations, some other locality should take the waste. He accounts for the high rate of approval in Östhammar by the fact that the existing nuclear power station in the area created familiarity with the technology – but also by the “prolonged and open dialogue”.

Jacob Spangenberg (left) is the mayor of Östhammar and has proposed to the municipal parliament to forgo a referendum on the new repository. Åsa Lindstrand (right) is part of the minority in Östhammar that is against the repository, partly because of safety concerns. swissinfo.ch

People are just tired, reckons Åsa Lindstrand, a tax consultant and one of the few people in the town who still oppose the permanent repository. She concedes that Sweden needs to find a permanent repository for highly radioactive waste, but Östhammar was decided on “much too hastily”. She criticises the method of encasing the waste in copper. “This method is controversial among experts now, for one thing because copper can corrode,” she says. For these reasons, Lindstrand wanted a referendum despite the high approval ratings.

The information centre of the Swedish nuclear waste agency is located in the centre of Östhammar. There the head of communication, Simon Hoff, points out that the encasing method developed by Sweden is already in use in Finland. “We’re learning from their experience,” he says.

Hoff emphasises that Östhammar has the “necessary geological features” but also had shown “public approval of a potential location”. The location decision in Sweden was thus to some extent a political one.

Meanwhile, back in Switzerland

The Swedish permanent repository is to be built under an offshore island, 20 kilometres from Östhammar. The land where the entrance to the Swiss permanent repository is to be placed is close to several villages – some just across the German border. The German government has already indicated there is a need for further discussion. Twenty kilometres in the opposite direction is Zurich airport, the biggest in Switzerland.

On the area of land that has been selected there is a farm, which NAGRA sees as making way for administrative buildings. The owners will probably be forced to sell their land. The entire region is going to have to deal with the effects of a major building project for 15 years. Digging the hole in the earth is going to mean plenty of noise and traffic at the site.

While in Östhammar the prospect of new jobs has contributed to local acceptance, hardly anyone in Switzerland expects the workers will come from the region. The border is too close, and Swiss pay rates are too attractive.

When the location of Nördlich Lägern was announced, the Swiss public broadcaster, SRF, asked if the choice was a political one. Opposition in Nördlich Lägern has, after all, been more muted than in other places on the shortlist. NAGRA denied this. It said that in all three locations studied it found layers of opalinus clay. In Nördlich Lägern, the stretch of ground with this geologically robust material is the biggest and also the farthest from water. “So geology decided,” NAGRA said.

“Here democracy was cancelled,” says Werner Ebnöther. The retired computer scientist is one of the opposition in Nördlich Lägern. He recalls that as early as the 1980s there was an initial experimental dig here. There was a non-binding referendum: 104 citizens were against, only two were in favour.

Werner Ebnöther is against the construction of the deep geological repository. But he expects it to be built now, regardless of whether there is a nationwide referendum. swissinfo.ch

People in the region had long believed that they had escaped their fate, in fact. For decades, NAGRA was planning to build a permanent repository in central Switzerland. After a majority there voted it down in two referendums, the federal government deleted the cantonal veto from the legislation.

In about ten years, Swiss citizens should get to vote on this – but nationwide. Ebnöther is sure that the majority will be happy the facility is “not in their backyard”. That the permanent repository will eventually be built, he has little doubt.

Ebnöther says he trusts NAGRA, “but not 100%”. So he will continue to participate in the observers’ group and keep an eye on safety issues, as well as new technologies concerning the disposal of radioactive waste. “We owe that to the coming generations,” he says. In the observers’ group, opponents of the permanent repository have often had their suggestions implemented, even prior to the location decision.

Responsibility

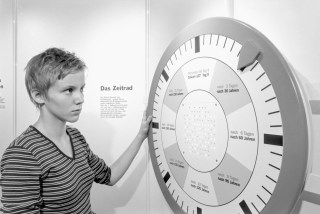

In the Mammoth Museum a few kilometres away, Andrea Weber walks over the geological ages of the earth marked out on the floor. She is co-director of safety in the observers’ group. She too speaks of responsibility. “One hundred thousand years is hard for anyone to imagine. Even our mammoth teeth here are only 45,000 years old.”

When she first heard that the permanent repository was likely to be located to this region, she took it “pragmatically” and was not defensive, she recalls. But she immediately realised that “we’ve got to ask lots of questions”. Questioning is part of responsibility, she says.

The observers’ group has existed for ten years. Here, government officials and representatives from the community discuss, share information and develop scenarios with the help of experts. It is to continue its work. There will perhaps be more and more interest now in getting involved.

Before the decision was announced, local interest was slight. In a representative survey in 2018 only 8% in Nördlich Lägern said they were “very concerned” about the possibility of a permanent repository in the region.

“From the beginning there was more acceptance in this region than elsewhere,” says mayor Dieter Schaltegger. “We trust the experts when they say that the decision was made for geological reasons.”

Does he think that in ten years a nationwide referendum will halt construction? “It could only delay it, and therefore put the responsibility for our waste off to the next generation.” He doesn’t want to gloss over the situation in any way, he says. He wants to take criticism on board, and work critically with the proposal.

In time, people in Nördlich Lägern may come to think as they do in Östhammar.

Edited by Mark Livingston. Translated from German by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Comments are closed.